John Peel

John Woodcock Graves: John Peel’s Boswell

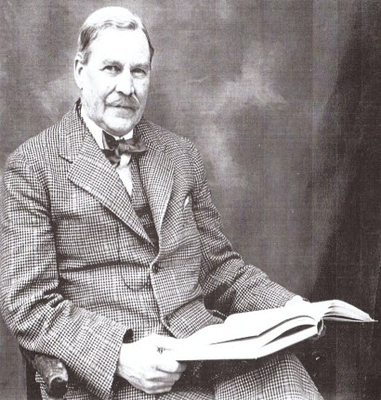

John Woodcock Graves (1795--1886)We’re all familiar with “John Peel,” surely the most well-known foxhunting song of all time. We’re perhaps less familiar with the songwriter, John Woodcock Graves, who turns out to be a most fascinating and unpredictable character—rogue some might say—in his own way. We owe this insight into Graves' life to our Cumbrian friend, Ron Black, who sent us excerpts from A Ramblers Notebook at the English Lakes (H. D Rawnsley, 1902).

In an earlier article, Foxhunting Life describes that night in 1829 when John Woodcock Graves sat in his parlor in Caldbeck, in England’s Lake District, with John Peel. Peel was a farmer, horse dealer, and foxhunter whose hounds were highly celebrated by the local sheep farmers. From the adjoining room, Graves overheard his son's granny singing an ancient Irish melody to the child. Graves took that old melody and wrote a new set of lyrics to honor his friend, John Peel.

"I sang it to poor Peel," Graves wrote, "who smiled through a stream of tears which fell down his manly cheeks, and I well remember saying to him in a joking style, ‘By Jove, Peel, you’ll be sung when we’re both run to earth!'’

Just a few years after that cozy night, however, Graves became embroiled in a violent altercation with an employee, the aftermath of which induced him to leave England forever. His adventures were just beginning.

John Peel

"Peel's view-halloo would waken the dead" / Illustration by Frank Paton from "The Songs of Foxhunting" by Alexander Mackay-Smith, 1974

"Peel's view-halloo would waken the dead" / Illustration by Frank Paton from "The Songs of Foxhunting" by Alexander Mackay-Smith, 1974

Like Tom Moody, John Peel owes his celebrity to a song, though I am bound to say that the Cumberland huntsman was far more worthy of such a distinction than the Shropshire whipper-in. And what canny Cumbrian is there, the wide world over, whose heart is not stirred within him by the dear, familiar words and tune of “D'ye ken John Peel,” even as the hearts of his Scottish neighbours across the Border are stirred by “Auld Lang Syne”!

It has been sung in strange places, that famous Cumberland hunting-song. Its chorus rang out hearty and homely from the huts at Balaclava and the dreary trenches before Sebastopol. It cheered the spirits of the band of beleaguered heroes in the Residency at Lucknow. The future King of England, our jolly sport-loving Prince, has been known many a time to join lustily in its spirit-stirring chorus. I myself have heard it sung on the boards of Drury Lane by some seventy comely lasses, whose shapely figures, clad in the hunting costume of the other sex, made one of the prettiest pictures I ever saw upon the stage, and gave an effect to the song which roused the audience to enthusiasm.

And yet, world-famous as the song is, I don't suppose that one person in a thousand knows who wrote it, or has the faintest notion who or what John Peel was beyond the fact that he was fond of hunting. Indeed, I have often heard the question asked, whether John Peel was a real person or merely a mythical hero. Well, that question is easily answered.

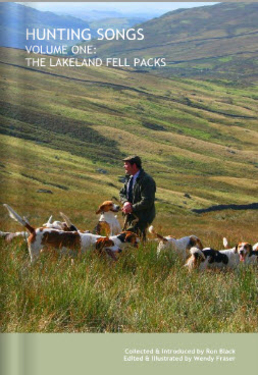

Hunting Songs, Volume One: The Lakeland Fell Packs

Hunting Songs, Volume One: The Lakeland Fell Packs, Ron Black and Wendy Fraser, Blurb Publishing, 2011, 75 pages, 7.50 pounds (soft cover), 15.50 pounds (hard cover), www.cumbrian-lad.comRon Black and Wendy Fraser collaborated on this collection—a folk history, really—of Lakeland hunting songs. Over the course of three-hundred years, followers of the fell packs of the English Lake District wrote these songs to memorialize historic runs, iconic huntsmen, special foxhounds, and—what pleased me especially—brave terriers! Perhaps I just never noticed, but I cannot recall any other book of hunting songs and poems that includes odes to these feisty little creatures.

Hunting Songs, Volume One: The Lakeland Fell Packs, Ron Black and Wendy Fraser, Blurb Publishing, 2011, 75 pages, 7.50 pounds (soft cover), 15.50 pounds (hard cover), www.cumbrian-lad.comRon Black and Wendy Fraser collaborated on this collection—a folk history, really—of Lakeland hunting songs. Over the course of three-hundred years, followers of the fell packs of the English Lake District wrote these songs to memorialize historic runs, iconic huntsmen, special foxhounds, and—what pleased me especially—brave terriers! Perhaps I just never noticed, but I cannot recall any other book of hunting songs and poems that includes odes to these feisty little creatures.

Or perhaps I paid special notice here because I now happen to be the smitten owner of a nine-month-old Border terrier whose ancestors scurried in their determined fashion over those same fells on the English-Scottish border. Here’s the story of Badger and Butcher by Mr. and Mrs. Curry, and it’s still sung today!

The Happiest Man in England

The happiest man in England rose an hour before the dawn;

The stars were in the purple and the dew was on the lawn;

He sang from bed to bathroom—he could only sing “John Peel”;

He donned his boots and breeches and he buckled on his steel.

He chose his brightest waistcoat and his stock with care he tied,

Though scarce a soul would see him in his early morning ride.

The Story of John Peel

MP3 audio download is at the bottom of this article. Subscribe or log in to hear and download the music!

One night in 1829, John Woodcock Graves sat in his parlor with John Peel, a farmer, horse dealer, and foxhunter whose hounds were highly celebrated by the local sheep farmers. From the adjoining room, Graves overheard his son's granny singing an ancient Irish melody to the child. Graves took that old melody and wrote a new set of lyrics to honor his friend, John Peel.

"I sang it to poor Peel," Graves wrote, "who smiled through a stream of tears which fell down his manly cheeks, and I well remember saying to him in a joking style, ‘By Jove, Peel, you’ll be sung when we’re both run to earth!’"

Forty years later, William Metcalfe, Choirmaster of Carlisle Cathedral, heard the song at a banquet. He set down the tune in musical notation for the first time together with Graves’ words, composed a piano accompaniment, and had it performed locally. He went on to London with his choir and on May 22, 1869 performed the song at the dinner of the Cumberland Benevolent Society from whence it spread quickly over the English-speaking world, propelling John Peel into the most famous foxhunter of all time.

The Story of John Peel

MP3 audio download is at the bottom of this article. Subscribe or log in to hear and download the music!

One night in 1829, John Woodcock Graves sat in his parlor with John Peel, a farmer, horse dealer, and foxhunter whose hounds were highly celebrated by the local sheep farmers. From the adjoining room, Graves overheard his son's granny singing an ancient Irish melody to the child. Graves took that old melody and wrote a new set of lyrics to honor his friend, John Peel.

"I sang it to poor Peel," Graves wrote, "who smiled through a stream of tears which fell down his manly cheeks, and I well remember saying to him in a joking style, ‘By Jove, Peel, you’ll be sung when we’re both run to earth!’"

Forty years later, William Metcalfe, Choirmaster of Carlisle Cathedral, heard the song at a banquet. He set down the tune in musical notation for the first time together with Graves’ words, composed a piano accompaniment, and had it performed locally. He went on to London with his choir and on May 22, 1869 performed the song at the dinner of the Cumberland Benevolent Society from whence it spread quickly over the English-speaking world, propelling John Peel into the most famous foxhunter of all time.

New From FHL: Music, Lyrics, and Audio Downloads

Before TV, video games, and texting, foxhunters used to entertain themselves with stories, poems, and songs. Foxhunting families would often break into song at the table after dinner, and windows rattled at many a hunt breakfast with songs of foxhunting.

Before TV, video games, and texting, foxhunters used to entertain themselves with stories, poems, and songs. Foxhunting families would often break into song at the table after dinner, and windows rattled at many a hunt breakfast with songs of foxhunting.

My good friend Caroline Treviranus Leake remembers impromptu songfests at the dinner table led by her step-father, the late Alexander Mackay-Smith. The entire family—mother Marilyn and sisters Denya and Leslie—would join in. Caroline remembers those times with the greatest of pleasure—times of togetherness, good cheer, and shared enjoyment.