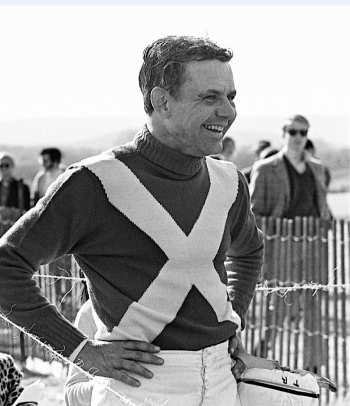

At the Piedmont Point-to-Point in the 1970s / Douglas Lees photoDr. Joseph Megeath Rogers, 90, died on Saturday, March 8, 2014 at his Hillbrook Farm near Hamilton following a stroke. While he occupied a gigantic space in the world of foxhunting, that world was but a small part of his very full, productive, and generous life.

At the Piedmont Point-to-Point in the 1970s / Douglas Lees photoDr. Joseph Megeath Rogers, 90, died on Saturday, March 8, 2014 at his Hillbrook Farm near Hamilton following a stroke. While he occupied a gigantic space in the world of foxhunting, that world was but a small part of his very full, productive, and generous life.

Physician, farmer, Master of Foxhounds, steeplechase rider and trainer, businessman, rural land conservationist, and philanthropist, Dr. Rogers was a tireless advocate and practitioner of country living whose contributions in a broad range of interests were made quietly and with little fanfare.

His public persona was most closely connected with remarkable success as an owner, trainer, and rider of some of Virginia’s most successful steeplechase horses running under his familiar red with white cross sash silks. But his success in that rugged and dangerous sport was merely a visible extension of his commitment to protect Virginia’s rural countryside, a mission he often defined as a moral obligation.

In pursuing that connection between equestrian sport and countryside preservation, he was a founder of the Oatlands Point-To-Point of the Loudoun Hunt, as well as of the Morven Park Steeplechase—the latter being the first race meet in the modern history of Virginia to offer pari-mutuel wagering.

A long time member of the Board of Directors of the Westmoreland Davis Foundation, which operates the historic Morven Park estate north of Leesburg, Dr. Rogers was also a founder of the Morven Park Equestrian Institute, as well as a founder of the Loudoun County Pony Club, a founding director of the Museum of Hounds and Hunting and a founding director of the American Academy of Equine Artists.

A soft-spoken and oftentimes shy man who preferred to get things done quietly, Dr. Rogers occasionally found himself somewhat self-consciously thrust into the limelight. Among those occasions was when he managed to retire the Virginia Gold Cup, considered the most prestigious timber race in Virginia, with three different horses, an accomplishment that defied almost any known odds in that unpredictable sport. One of those Gold Cup-winning horses, King of Spades, became the subject of a song recorded by the legendary bluegrass band, The Country Gentlemen. King of Spades had attracted such an enormous following among steeplechase enthusiasts that, when he was killed in a freak paddock accident, one newspaper published an obituary on him as though he was a prominent Loudoun County citizen.

Joe Rogers aboard King of Spades at the Piedmont Point-to-Point, 1971 / Douglas lees photo

Joe Rogers aboard King of Spades at the Piedmont Point-to-Point, 1971 / Douglas lees photo

Another occasion that drew public attention to Dr. Rogers was when the Loudoun Times Mirror named him Man of The Year in the 1990s, an honor usually bestowed on people who had cultivated a much higher public profile. Ironically, Dr. Rogers only a few years earlier was the initial investor in a successful start-up newspaper called Leesburg Today which was in direct competition with the Times-Mirror. But the owner of the Times-Mirror, Arthur W. Arundel, was a long-time friend and the two had collaborated on a number of important rural land preservation efforts, including promoting the establishment of conservation easements that led to thousands of acres of Virginia countryside being permanently preserved against development. Their racehorses had also competed with some regularity over the years, and they shared an enduring love of foxhunting. When faced with a friendly warning by Mr. Arundel that he would “lose your shirt” investing in a start-up competitor to the venerable Times-Mirror, Dr. Rogers grinned and replied, “well, Nick, I’ve got lots of shirts.” They remained good friends.

The family-owned Wilkins Rogers Milling Company was a source of considerable wealth to the four Rogers brothers. Dr. Rogers’ business interests also extended to being the former owner of the Loudoun County Milling Company, a director of Farmers & Merchants National Bank and a past director and officer of Earthwork, Inc.

After graduating in 1947 from the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Dr. Rogers returned to Loudoun and set up a private practice that included among his patients both the prominent and the indigent. He routinely made house calls to tend to patients who he knew could not afford to pay him, but to whom he felt an obligation because many of them were the men and women who worked on the farms of Loudoun. His medical career in Loudoun started at a time when the county had a population of less than 30,000 and only a handful of physicians. He often said of his medical practice that it was the way he chose to give back to a community where his family roots ran deep. That sense of obligation led him at one point to become Chief of Staff at Loudoun Memorial Hospital, and he finished out his medical career by serving as chief of the emergency room at the same facility. He also served as a Director of the Loudoun Healthcare Foundation, was on the advisory board of the Loudoun Senior Citizens Association, and was a volunteer with the Loudoun Food Closet—all of them in one way or another working to see to the health of Loudoun citizens.

His medical interests were not limited to the human variety. He was Vice Chairman of the Founders Committee of the Marion duPont Scott Equine Veterinary College at Morven Park, a unique partnership between the University of Maryland and Virginia Tech. He was also a pioneer in what later became known as aerobic training of racehorses. He set up measured training segments on Hillbrook and would work his steeplechase horses over those segments, timing each and then using a stethoscope to measure the horses’ heart rates. As his horses became more fit, their segment times improved and their heart rates came down—carefully calculated proof of the steadily improving endurance. That training methodology produced what became a devastating ability of Rogers-trained horses to race well off the early pace, then close with a rush at the end when the competition was used up and his own horses were drawing on the aerobic conditioning painstakingly developed and recorded at Hillbrook.

The 1200 acre Hillbrook Farm located on Harmony Church Road south of Hamilton was both a thriving agricultural business and a personal haven for Dr. Rogers. He preserved the land forever by placing it in open space conservation easements He bred Angus cattle, produced hay and other crops, developed his racing stock, and tended to foxhounds—the latter an extension of his longtime role as Master of Foxhounds for the Loudoun Hunt, later becoming the Loudoun Hunt West. The main residence at Hillbrook, while modest in size compared to some of Virginia’s more elaborate mansions, became a virtual museum of racing, farming and agricultural literature under his care and that of his wife, Donna. To a visitor, his deep knowledge and obvious love of Virginia life would emerge one measured sentence at a time as he sat in his favorite old red leather chair in the den at Hillbrook.

His knowledge of productive farming—and the dangers it faced in a rapidly developing Northern Virginia—propelled him to service in a wide variety of organizations with influence in the field of agriculture. Among them were the Loudoun Soil and Water Conservation District, the Loudoun Rural Area Development Committee, the Loudoun Rural Area Management Plan Committee, the Piedmont Environmental Council, the Loudoun County Tax Advisory Board, the Loudoun County Historical Society and the Goose Creek Historic District.

He was also a founder of the Bedford Fund—named in honor of his long time friend and fellow land preservationist Erskine Bedford—which was dedicated to promoting the placement of conservation easements on rural land. He was also a member of the Catoctin Farmers Club, whose roster was a Who’s Who of family names representing ownership of hundreds of thousand of acres of productive farmland west of Goose Creek in the days when Loudoun was among the state’s leaders in virtually every category of agriculture. He was also an underwriter of the Country Life Center’s project to develop a Rural Economic Development zone that would put an agriculture-based financial footing under western Loudoun land facing heavy residential development pressure. Some of the provisions in that model project created the county’s regulatory framework promoting the establishment and expansion of today’s flourishing winery industry in Loudoun.

When a public policy matter involving rural land conservation came to his attention, he did not venture to Leesburg to publicly lecture the county’s elected leaders on its importance. He would instead invite one or two to have a meal with him at Hillbrook, where he would listen carefully to the issue being discussed, then present his own thoughts, and thank the visitors for coming.

“When you want to get your point across, you don’t do it by embarrassing other people,” he once told a journalist.

His contributions to the organizational side of equine sport were also significant, having served as founder and director of the Virginia Steeplechase Association, as a senior steward of the National Steeplechase Association, and as founder and life member of the United States Combined Training Association, which is America’s Olympic training organization for equine sports.

Dr. Rogers is survived by his wife Donna Truslow Rogers, brothers Samuel Hamilton Rogers, Jr. and Richard Alexander Rogers; his children Marilyn Ashby Rogers Renner, Joseph Megeath Rogers, Jr., and Elizabeth Rogers Villeda; and his granddaughter Hannah Megeath Rogers Tucker. His brother Howard Cochran Rogers predeceased him.

Services will be held on Wednesday March 12, 2014 at 2:00 pm at St. James Episcopal Church in Leesburg. Burial will be in Union Cemetery.

In lieu of flowers memorial contributions may be made to Land Trust of Virginia, P.O. Box 14, Middleburg, VA 20118, Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center, 17690 Old Waterford Road, Leesburg, VA 20176 and Museum of Hounds and Hunting, Morven Park, P.O. Box 6228, Leesburg, VA 20178-7433.

[Dr. Rogers was a life long friend and mentor to the author of this article.]

Posted March 10, 2014