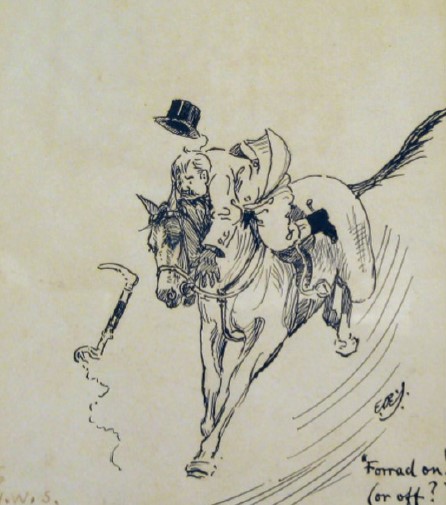

“…made me feel as if I were being skillfully kicked downstairs.” / Illustration by Edith Somerville

“…made me feel as if I were being skillfully kicked downstairs.” / Illustration by Edith Somerville

This week’s Bonus article, free to all (no subscription necessary), finds Major Sinclair Yeates, R.M. (Resident Magistrate) posted to Ireland by the British Crown with the authority to adjudicate local disputes. He rents a house, Shreelane, for himself and his wife-to-be, Philippa, from Mr. Flurry Knox, Master of the local pack of foxhounds.

No one can accuse Philippa and me of having married in haste. As a matter of fact, it was but little under five years from that autumn evening on the river when I had said what is called in Ireland “the hard word,” to the day in August when I was led to the altar by my best man, and was subsequently led away from it by Mrs. Sinclair Yeates. About two years out of the five had been spent by me at Shreelane in ceaseless warfare with drains, eaveshoots, chimneys, pumps; all those fundamentals, in short, that the ingenuous and improving tenant expects to find established as a basis from which to rise to higher things. As far as rising to higher things went, frequent ascents to the roof to search for leaks summed up my achievements; in fact, I suffered so general a shrinkage of my ideals that the triumph of making the hall-door bell ring blinded me to the fact that the rat-holes in the hall floor were nailed up with pieces of tin biscuit boxes, and that the casual visitor could, instead of leaving a card, have easily written his name in the damp on the walls.

Philippa, however, proved adorably callous to these and similar shortcomings. She regarded Shreelane and its floundering, foundering ménage of incapables in the light of a gigantic picnic in a foreign land; she held long conversations daily with Mrs. Cadogan, in order, as she informed me, to acquire the language; without any ulterior domestic intention she engaged kitchen-maids because of the beauty of their eyes, and housemaids because they had such delightfully picturesque old mothers, and she declined to correct the phraseology of the parlour-maid, whose painful habit it was to whisper “Do ye choose

cherry or clarry?” when proffering the wine. Fast-days, perhaps, afforded my wife her first insight into the sterner realities of Irish housekeeping. Philippa had what are known as High Church proclivities, and took the matter seriously.

The visit to which we owed our escape from the intricacies of the fast-day was to the Knoxes of Castle Knox, relations in some remote and tribal way of my landlord, Mr. Flurry of that ilk. It involved a short journey by train, and my wife’s longest basket-trunk; it also, which was more serious, involved my being lent a horse to go out cubbing the following morning.

At Castle Knox we sank into an almost forgotten environment of draught-proof windows and doors, of deep carpets, of silent servants instead of clattering belligerents. I had the good fortune to be of the limited number of those who got on with Lady Knox, chiefly, I imagine, because I was as a worm before her, and thankfully permitted her to do all the talking.

“Your wife is extremely pretty,” she pronounced autocratically, surveying Philippa between the candle-shades; “does she ride?” Lady Knox was a short square lady, with a weather-beaten face, and an eye decisive from long habit of taking her own line across country and elsewhere. She would have made a very imposing little coachman, and would have caused her stable helpers to rue the day they had the presumption to be born; it struck me that Sir Valentine sometimes did so.

“I’m glad you like her looks,” I replied, “as I fear you will find her thoroughly despicable otherwise; for one thing, she not only can’t ride, but she believes that I can!”

“Oh come, you’re not as bad as all that!” my hostess was good enough to say; “I’m going to put you up on Sorcerer to-morrow, and we’ll see you at the top of the hunt—if there is one. That young Knox hasn’t a notion how to draw these woods.”

“Well, the best run we had last year out of this place was with Flurry’s hounds,” struck in Miss Sally, sole daughter of Sir Valentine’s house and home, from her place half-way down the table. It was not difficult to see that she and her mother held different views on the subject of Mr. Flurry Knox.

“I call it a criminal thing in any one’s great-great-grandfather to rear up a preposterous troop of sons and plant them all out in his own country,” Lady Knox said to me with apparent irrelevance. “I detest collaterals. Blood may be thicker than water, but it is also a great deal nastier. In this country I find that fifteenth cousins consider themselves near relations if they live within twenty miles of one!”

Having before now taken in the position with regard to Flurry Knox, I took care to accept these remarks as generalities, and turned the conversation to other themes.

“I see Mrs. Yeates is doing wonders with Mr. Hamilton,” said Lady Knox presently, following the direction of my eyes, which had strayed away to where Philippa was beaming upon her left-hand neighbour, a mildewed-looking old clergyman, who was delivering a long dissertation, the purport of which we were happily unable to catch.

“She has always had a gift for the Church,” I said.

As I struggled into my boots the following morning, I felt that Sir Valentine’s acid confidences on cub-hunting, bestowed on me at midnight, did credit to his judgment. “A very moderate amusement, my dear Major,” he had said, in his dry little voice; “you should stick to shooting. No one expects you to shoot before daybreak.”

It was six o’clock as I crept downstairs, and found Lady Knox and Miss Sally at breakfast, with two lamps on the table, and a foggy daylight oozing in from under the half-raised blinds. Philippa was already in the hall, pumping up her bicycle, in a state of excitement at the prospect of her first experience of hunting that would have been more comprehensible to me had she been going to ride a strange horse, as I was. As I bolted my food I saw the horses being led past the windows, and a faint twang of a horn told that Flurry Knox and his hounds were not far off.

Miss Sally jumped up. “If I’m not on the Cockatoo before the hounds come up, I shall never get there!” she said, hobbling out of the room in the toils of her safety habit. Her small, alert face looked very childish under her riding-hat; the lamp-light struck sparks out of her thick coil of golden-red hair: I wondered how I had ever thought her like her prim little father.

She was already on her white cob when I got to the hall-door, and Flurry Knox was riding over the glistening wet grass with his hounds, while his whip, Dr. Jerome Hickey, was having a stirring time with the young entry and the rabbit-holes. They moved on without stopping, up a back avenue, under tall and dripping trees, to a thick laurel covert, at some little distance from the house. Into this the hounds were thrown, and the usual period of fidgety inaction set in for the riders, of whom, all told, there were about half-a-dozen. Lady Knox, square and solid, on her big, confidential iron-grey, was near me, and her eyes were on me and my mount; with her rubicund face and white collar she was more than ever like a coachman.

“Sorcerer looks as if he suited you well,” she said, after a few minutes of silence, during which the hounds rustled and crackled steadily through the laurels; “he’s a little high on the leg, and so are you, you know, so you show each other off.”

Sorcerer was standing like a rock, with his good-looking head in the air and his eyes fastened on the covert. His manners, so far, had been those of a perfect gentleman, and were in marked contrast to those of Miss Sally’s cob, who was sidling, hopping, and snatching unappeasably at his bit. Philippa had disappeared from view down the avenue ahead. The fog was melting, and the sun threw long blades of light through the trees; everything was quiet, and in the distance the curtained windows of the house marked the warm repose of Sir Valentine, and those of the party who shared his opinion of cubbing.

“Hark! hark to cry there!”

It was Flurry’s voice, away at the other side of the covert. The rustling and brushing through the laurels became more vehement, then passed out of hearing.

“He never will leave his hounds alone,” said Lady Knox disapprovingly. Miss Sally and the Cockatoo moved away in a series of heraldic capers towards the end of the laurel plantation, and at the same moment I saw Philippa on her bicycle shoot into view on the drive ahead of us.

“I’ve seen a fox!” she screamed, white with what I believe to have been personal terror, though she says it was excitement; “it passed quite close to me!”

“What way did he go?” bellowed a voice which I recognised as Dr. Hickey’s, somewhere in the deep of the laurels.

“Down the drive!” returned Philippa, with a pea-hen quality in her

tones with which I was quite unacquainted.

An electrifying screech of “Gone away!” was projected from the laurels

by Dr. Hickey.

“Gone away!” chanted Flurry’s horn at the top of the covert.

“This is what he calls cubbing!” said Lady Knox, “a mere farce!” but none the less she loosed her sedate monster into a canter.

Sorcerer got his hind-legs under him, and hardened his crest against the bit, as we all hustled along the drive after the flying figure of my wife. I knew very little about horses, but I realised that even with the hounds tumbling hysterically out of the covert, and the Cockatoo kicking the gravel into his face, Sorcerer comported himself with the manners of the best society. Up a side road I saw Flurry Knox opening half of a gate and cramming through it; in a moment we also had crammed through, and the turf of a pasture field was under our feet. Dr. Hickey leaned forward and took hold of his horse; I did likewise, with the trifling difference that my horse took hold of me, and I steered for Flurry Knox with single-hearted purpose, the hounds, already a field ahead, being merely an exciting and noisy accompaniment of this endeavour.

A heavy stone wall was the first occurrence of note. Flurry chose a place where the top was loose, and his clumsy-looking brown mare changed feet on the rattling stones like a fairy. Sorcerer came at it, tense and collected as a bow at full stretch, and sailed steeply into the air; I saw the wall far beneath me, with an unsuspected ditch on the far side, and I felt my hat following me at the full stretch of its guard as we swept over it, then, with a long slant, we descended to earth some sixteen feet from where we had left it, and I was possessor of the gratifying fact that I had achieved a good-sized “fly,” and had not perceptibly moved in my saddle. Subsequent disillusioning experience has taught me that but few horses jump like Sorcerer, so gallantly, so sympathetically, and with such supreme mastery of the subject; but none the less the enthusiasm that he imparted to me has never been extinguished, and that October morning ride revealed to me the unsuspected intoxication of fox-hunting.

Behind me I heard the scrabbling of the Cockatoo’s little hoofs among the loose stones, and Lady Knox, galloping on my left, jerked a maternal chin over her shoulder to mark her daughter’s progress. For my part, had there been an entire circus behind me, I was far too much occupied with ramming on my hat and trying to hold Sorcerer, to have looked round, and all my spare faculties were devoted to steering for Flurry, who had taken a right-handed turn, and was at that moment surmounting a bank of uncertain and briary aspect. I surmounted it also, with the swiftness and simplicity for which the Quaker’s methods of bank jumping had not prepared me, and two or three fields, traversed at the same steeplechase pace, brought us to a road and to an abrupt check. There, suddenly, were the hounds, scrambling in baffled silence down into the road from the opposite bank, to look for the line they had overrun, and there, amazingly, was Philippa, engaged in excited converse with several men with spades over their shoulders.

“Did ye see the fox, boys?” shouted Flurry, addressing the group.

“We did! we did!” cried my wife and her friends in chorus; “he ran up the road!”

“We’d be badly off without Mrs. Yeates!” said Flurry, as he whirled his mare round and clattered up the road with a hustle of hounds after him.

It occurred to me as forcibly as any mere earthly thing can occur to those who are wrapped in the sublimities of a run, that, for a young woman who had never before seen a fox out of a cage at the Zoo, Philippa was taking to hunting very kindly. Her cheeks were a most brilliant pink, her blue eyes shone.

“Oh, Sinclair!” she exclaimed, “they say he’s going for Aussolas, and there’s a road I can ride all the way!”

“Ye can, Miss! Sure we’ll show you!” chorussed her cortège.

Her foot was on the pedal ready to mount. Decidedly my wife was in no need of assistance from me.

Up the road a hound gave a yelp of discovery, and flung himself over a stile into the fields; the rest of the pack went squealing and jostling after him, and I followed Flurry over one of those infinitely varied erections, pleasantly termed “gaps” in Ireland. On this occasion the gap was made of three razor-edged slabs of slate leaning against an iron bar, and Sorcerer conveyed to me his thorough knowledge of the matter by a lift of his hind-quarters that made me feel as if I were being skilfully kicked downstairs. To what extent I looked it, I cannot say, nor providentially can Philippa, as she had already started. I only know that undeserved good luck restored to me my stirrup before Sorcerer got away with me in the next field.

What followed was, I am told, a very fast fifteen minutes; for me time was not; the empty fields rushed past uncounted, fences came and went in a flash, while the wind sang in my ears, and the dazzle of the early sun was in my eyes. I saw the hounds occasionally, sometimes pouring over a green bank, as the charging breaker lifts and flings itself, sometimes driving across a field, as the white tongues of foam slide racing over the sand; and always ahead of me was Flurry Knox, going as a man goes who knows his country, who knows his horse, and whose heart is wholly and absolutely in the right place.

Do what I would, Sorcerer’s implacable stride carried me closer and closer to the brown mare, till, as I thundered down the slope of a long field, I was not twenty yards behind Flurry. Sorcerer had stiffened his neck to iron, and to slow him down was beyond me; but I fought his head away to the right, and found myself coming hard and steady at a stonefaced bank with broken ground in front of it. Flurry bore away to the left, shouting something that I did not understand. That Sorcerer shortened his stride at the right moment was entirely due to his own judgment; standing well away from the jump, he rose like a stag out of the tussocky ground, and as he swung my twelve stone six into the air the obstacle revealed itself to him and me as consisting not of one bank but of two, and between the two lay a deep grassy lane, half choked with furze. I have often been asked to state the width of the bohereen, and can only reply that in my opinion it was at least eighteen feet; Flurry Knox and Dr. Hickey, who did not jump it, say that it is not more than five. What Sorcerer did with it I cannot say; the sensation was of a towering flight with a kick back in it, a biggish drop, and a landing on cee-springs, still on the downhill grade. That was how one of the best horses in Ireland took one of Ireland’s most ignorant riders over a very nasty place.

A sombre line of fir-wood lay ahead, rimmed with a grey wall, and in another couple of minutes we had pulled up on the Aussolas road, and were watching the hounds struggling over the wall into Aussolas demesne.

“No hurry now,” said Flurry, turning in his saddle to watch the Cockatoo jump into the road, “he’s to ground in the big earth inside. Well, Major, it’s well for you that’s a big-jumped horse. I thought you were a dead man a while ago when you faced him at the bohereen!”

I was disclaiming intention in the matter when Lady Knox and the others joined us.

“I thought you told me your wife was no sportswoman,” she said to me, critically scanning Sorcerer’s legs for cuts the while, “but when I saw her a minute ago she had abandoned her bicycle and was running across country like—”

“Look at her now!” interrupted Miss Sally. “Oh!—oh!” In the interval between these exclamations my incredulous eyes beheld my wife in mid-air, hand in hand with a couple of stalwart country boys, with whom she was leaping in unison from the top of a bank on to the road.

Every one, even the saturnine Dr. Hickey, began to laugh; I rode back to Philippa, who was exchanging compliments and congratulations with her escort.

“Oh, Sinclair!” she cried, “wasn’t it splendid? I saw you jumping, and everything! Where are they going now?”

“My dear girl,” I said, with marital disapproval, “you’re killing yourself. Where’s your bicycle?”

“Oh, it’s punctured in a sort of lane, back there. It’s all right; and then they”—she breathlessly waved her hand at her attendants—”they showed me the way.”

“Begor! you proved very good, Miss!” said a grinning cavalier.

“Faith she did!” said another, polishing his shining brow with his white flannel coat-sleeve, “she lepped like a haarse!”

“And may I ask how you propose to go home?” said I.

“I don’t know and I don’t care! I’m not going home!” She cast an entirely disobedient eye at me. “And your eye-glass is hanging down your back and your tie is bulging out over your waistcoat!”

The little group of riders had begun to move away.

“We’re going on into Aussolas,” called out Flurry; “come on, and make my grandmother give you some breakfast, Mrs. Yeates; she always has it at eight o’clock.”

The front gates were close at hand, and we turned in under the tall beech-trees, with the unswept leaves rustling round the horses’ feet, and the lovely blue of the October morning sky filling the spaces between smooth grey branches and golden leaves. The woods rang with the voices of the hounds, enjoying an untrammelled rabbit hunt, while the Master and the Whip, both on foot, strolled along unconcernedly with their bridles over their arms, making themselves agreeable to my wife, an occasional touch of Flurry’s horn, or a crack of Dr. Hickey’s whip, just indicating to the pack that the authorities still took a friendly interest in their doings.

Posted May 25, 2020

The conclusion of our abridged version of the chapter “Phillipa’s Fox Hunt,” extracted from Some Experiences of an Irish R.M. by Somerville and Ross, will appear in the next issue.